Photograph courtesy Luton Hoo Estate.

The Luton Hoo Walled Garden

and its mysteries

Photograph courtesy Luton Hoo Estate.

Introduction

The Luton Hoo walled garden is a part of the original Luton Hoo estate near Luton, Bedfordshire. It was set up by John Stuart, the third Earl of Bute[i] in the 18thC and developed in a variety of ways ever since. Only a few other octagonal walled gardens are known in Britain (see Appendix) none of which compares to that at Luton Hoo. The reason for that shape is not known, nor is why it the Hoo garden is not quite a true regular octagon but is instead slightly flattened at the Southern end. This page presents a summary of some possibly relevant facts and conjectures that might explain some or all of these unknowns.

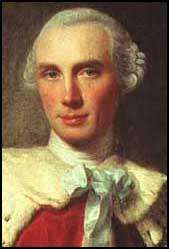

The Earl of Bute (courtesy of Wikipedia and other sources[ii])

The third Earl of Bute studied at Eton College (1720–1728) and the University of Leiden, Netherlands (1728–1732), where he graduated with a degree in civil and public law. He was a member of Sir Francis Dashwood's "Hell Fire Club" in Buckinghamshire[iii]. Bute served as Prime Minister of Great Britain (1762–1763) under George III, and was arguably the last important favourite in British politics. He was the first Prime Minister from Scotland following the Acts of Union in 1707.

On

24 August 1736, he married Mary Wortley Montagu[iv]

(daughter of Sir Edward and Lady Mary Wortley Montagu). Prior to his marriage,

he was not wealthy and his father-in-law (who it seems was ‘careful with his

money’) unsuccessfully attempted to prevent the marriage. Bute acquired all his

wife's wealth upon his marriage, since this was the law at that time[v]

.

On

24 August 1736, he married Mary Wortley Montagu[iv]

(daughter of Sir Edward and Lady Mary Wortley Montagu). Prior to his marriage,

he was not wealthy and his father-in-law (who it seems was ‘careful with his

money’) unsuccessfully attempted to prevent the marriage. Bute acquired all his

wife's wealth upon his marriage, since this was the law at that time[v]

.

In 1737, he was elected a Scottish representative peer, but he was not very active in the Lords and he was not re-elected in 1741. For the next few years he retired to Scotland to manage his estates and develop his botanical interests.

During the Jacobite Rebellion of 1745, Bute moved to Westminster in London. In 1754, he bought a house on Kew Green and built an extension there to accommodate his botanical library. The house had a private gate into the grounds of Kew Palace where he helped Princess Augusta to create Kew Gardens. The following year, he was appointed as tutor to Prince George the ‘new’ Prince of Wales. As a part of these duties, Bute arranged for the Prince and his brother Prince Edward to attend lectures/talks on natural philosophy. This led to an increased interest in the subject on the part of the young prince and was one in a series of events that led to the establishment of the George III Collection of Natural Philosophical Instruments.

In March 1761 he was appointed one of HM’s Principal Secretaries of State and in the following June, Ranger of Richmond Park. The following August he was appointed one of the governors of ‘The Charter House’ and in the same month he was elected Chancellor of the University of Aberdeen and to the Castle Hill Observatory to which he later donated two telescopes. In 1780 he was elected as the founding President of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland.

These combined interests of botany, astronomy and philosophical instruments appear to be significant in the concepts behind the walled garden.

After George's accession to the throne in 1760 and because of his connections, Bute might have expected soon to rise to political power, but this was not to be achieved so quickly. Re-elected as a Scottish representative peer in 1760, he was appointed the de-facto Prime Minister, and was successful in ending the Whig dominance and the Seven Years' War, but King George began to see through him. Bute resigned as prime minister shortly afterwards, though he remained in the House of Lords as a Scottish representative peer until 1780. He was relieved to give up public office because he had not had the support of his colleagues, he was extremely unpopular with the public and was greatly disliked in Parliament.

Bute bought the Luton Hoo estate in Bedfordshire in 1763[vi] and went to live there about the end of that year. He continued to sit in the House of Lords. However, ill health caused him to travel in Europe between 1768 and 1771. In 1773 he bought land near Christchurch in Hampshire and built Highcliffe House, overlooking the sea. In 1780, he retired from Parliament because of his age when he was 67. In November 1790 he slipped and fell about 30 feet down the cliffs at Highcliffe whilst collecting plants. This fall is thought to have contributed to his death in March 1792[vii].

Prior to living in Hampshire, and presumably whilst living on the Luton estate, the Earl had (what is now) Luton Hoo designed and built by Robert Adam. Work started in 1767. The original plan had been for a grand and magnificent new house. However, this plan was never fully executed and much of the work was a remodelling of the older house. Building work was interrupted by a fire in 1771, but by 1774 the new house, though incomplete, was inhabited.

While Adam was working on the mansion the landscape gardener Capability Brown, in what was the first entry mentioned in his then new account book[viii], was enlarging and redesigning the park, formerly approximately 300 acres (1.2 km²) it was now enlarged to 1,200 acres (4.9 km²). Brown dammed the River Lea to form two lakes, one of which is 60 acres (240,000 m²) in size.

In 1781 Samuel Johnson is said to have visited the house and is quoted as saying, "This is one of the places I do not regret coming to see...in the house magnificence is not sacrificed to convenience, nor convenience to magnificence".

So it seems that the Earl lived on the Luton Hoo estate in the period 1763 to (say) 1775 with a three year sojourn overseas between 1768 and 1771.

The Origin of the Walled Garden

In the original plans for Luton Hoo, provision was made to develop a walled garden. This was originally to be sited by the river - presumably because of the proximity of water and the availability of a sheltered location. An early print of the plans shows the garden as having rows of beds in an irregular parallelogram shape and possibly not even with a surrounding wall, rather as described by Gray[ix]

At some point Bute appears to have changed the plans for this garden and he had it moved to the other side of the house and placed some 63 metres (207 feet) higher in altitude to what is one of the highest points on the estate.

The reasons for this change of location are less clear. It may simply have been that the first proposed site could have been viewed - and maybe even smelt! - from the house, though Brown was very attuned to the proper selection and control of all vistas and this might be considered unlikely. Another more recent (2018) discovery is that the river feeding the garden had recently flooded and that the valley there was in any case prone to mists that would have enveloped the then garden. The old overshot waterwheel house has recently been identified as the means by which water was pumped from the river to the Main House, nearby farms and to the site of the (new) walled garden.

A five acre garden is very large indeed. For example, Wilson[x] describes a four acre garden as ‘very large’. There must have been good reason to move a five acre garden away from any supply of water and to place it on a much higher elevation to a place where the North side is 164m above sea level and its South side is 2m below that so providing gentle southerly drainage. Once completed, the garden was second only to the Royal Botanic Garden, Kew. Initially a botanical garden, it also was the ideal place from which to grow soft fruits and that later developed into the production centre for the estate’s fruit, vegetable and cut flower requirements lasting nearly two centuries. A reliable microclimate would indeed have been necessary.

A fundamental reason for the move of the garden must surely have been connected with the

Earl’s botanical and horticultural interests and maybe the reason was connected

with the need to maximise sunlight from its higher location. However Campbell[xi]

says:

"Before the early eighteenth century the best situation for a walled kitchen

garden was considered to be close to the house.... But with the advent, early in

the eighteenth century, of the landscaped park and garden, the proximity of a

high-walled kitchen garden tended to be detrimental to the view from the

mansion.... On large estates... the kitchen garden might be relocated as much as

a mile or more away, where it would not only be invisible from the house but

also possibly benefit from a more suitable site."

Then Wilson[xii] says:

"By [the late C18/early C19] the kitchen gardens of many country houses were being relocated far from their earlier position behind the house or next door to the flower garden. Sites were chosen, where possible, with a warm south-sloping aspect to encourage early ripening of the produce. Ideally the longer walls ran east to west, giving plenty of south-facing wall space for fruit trees. But the other walls could be used to advantage for later-ripening varieties, thus extending the season.... But eventually the season for enjoying fresh fruit and delicate vegetables was extended almost indefinitely by the development of the elaborate system of heated greenhouses maintained in the kitchen gardens of Victorian times." (Wilson p. 4)

In its new south-sloping position the garden certainly needed a wall to provide protection from the wind and an octagonal shape was devised. Much later years the walls were increased in height and an elaborate water supply system was installed using pipes laid all around along the top of the walls with down pipes and taps at regular intervals. The high walls protected the garden from thieves, created a micro-climate of warmth and calm within and would have permited fan-trained trees to be grown against them.

Recent research (2018) gives further credence to the idea that a key purpose of the then 'new' Walled Garden was indeed to grow soft fruits - particularly to accommodate the growing interest in the latest fruits recently brought to England like peaches, nectarines etc.

But why the Octagonal Shape?

According to Campbell[xiii] there is an oval garden at Gravetye, East Sussex, an Hexagonal one at Herriard, Southampton with inbuilt fruit walls, Crinkle-Crankle walls at Deans Court, Wimborne Minster and even heated walls at Tatton Park in Cheshire. There are few other octagonal walled gardens in Britain either before or since. It is interesting therefore to consider why such a shape might have been chosen.

Lord Bute’s astronomical interests may have played a part. The Greenwich Observatory after all had used Christopher Wren’s Octagonal viewing room since 1676. This allowed all directions of the sky to be observed and interestingly the window in one wall of that room faces due North – in the same alignment as one wall of the walled garden.

Again the shape may well have been a novel attempt to provide a wider selection of wall angles for his botanical garden. We know from Campbell[xiv] that just for fruit:

"The best, south-facing walls were dedicated to apricots, peaches and nectarines. Acid fruits... as well as late varieties of plums and pears, were given north-facing walls. Sweet cherries, early plums, apples and figs faced east. More peaches, greengages and early pears faced west." (Campbell, 2006, pp.27-28)

![]() Not

only this but we must not forget that the garden was being assembled only some

twenty or so years after the introduction of the infamous Glass Tax (1746)

on top of the earlier infamous Window Tax (1696-1851).

This had a major effect in all sorts of areas, even down to the introduction of

hollow stemmed "Excise drinking glasses" and the octagonal shape of the

garden might well have been some sort of alternative to providing a greenhouse.

However we know from a map of 1826 that by then the octagonal garden included a

conservatory - yet the glass tax was only abolished by Sir Robert Peel's

government in 1845.

Not

only this but we must not forget that the garden was being assembled only some

twenty or so years after the introduction of the infamous Glass Tax (1746)

on top of the earlier infamous Window Tax (1696-1851).

This had a major effect in all sorts of areas, even down to the introduction of

hollow stemmed "Excise drinking glasses" and the octagonal shape of the

garden might well have been some sort of alternative to providing a greenhouse.

However we know from a map of 1826 that by then the octagonal garden included a

conservatory - yet the glass tax was only abolished by Sir Robert Peel's

government in 1845.

|

|

|

©2013

Google Earth, ©2013 Infoterra Ltd & BlueSky |

The actual shape of the garden is not quite an exact octagon, see the first picture (left) where a true (that is to say a ‘regular’) octagonal shape has been superimposed as a black line, but viewing the night sky was not (as far as we know) an intended part of the use of the Walled Garden. As mentioned above a more likely possibility is that the garden was sited higher up so as to maximise the sunlight and to provide a variety of wall orientations for botanical reasons; but here another property of a North-South oriented Octagon comes to the fore.

This is that at the latitude of Luton Hoo the other walls of the Octagon curiously face (more or less) the directions of sunrise and sunset at the Spring and Autumn equinoxes and at the mid summer and mid-winter solstices too. These directions can be seen from the second picture. North is at the top. Some explanation may be in order.

The Solar alignments at Luton Hoo Walled Garden

We all know that the sun rises to the higher points of the sky in summer and to lower ones in winter. This is a consequence of the tilt of the earth’s axis. But it follows that in summer we see longer days, earlier sunrises and later sunsets. The opposite is true in winter. In the second image below a red line from the centre of the garden to the NE wall indicates the most northerly direction of sunrise – on June 21st mid-summer’s day. Similarly the red line from the centre to the NW wall indicates the most northerly direction of sunset at mid-summer.

The lines to the SE and SW walls of the garden show the directions of sunrise and sunset respectively for mid winter, December 21st. The lines to the East and West walls show the position of sunrise an sunset at the Equinoxes, 21st March and 21st September when the sun rises due East and sets due West with equal periods of day and night (hence the name equinox).

The Significance of the Solar Alignments

|

|

|

©2013 Google Earth, ©2013 Infoterra Ltd & BlueSky |

These alignments might sound a bit esoteric and indeed they might be a simple manifestation of the Earl’s interest in astronomy. However they also have a very practical purpose for those tending a garden since they indicate the progression of the seasons and, just as in earlier times, the position of the sun as it rises and sets can give gardeners a direct knowledge – without the need for supervision - of when to plant and when to gather-in the crops of whatever might be being grown at the time. In ancient times these positions were observed against the immediate horizon. In the case here, a simple glance at the direction of the sun against the walls of the garden would be sufficient and the eight walls would allow considerable precision in any such estimate.

Why might some sort of visual guide to the Seasons have been useful at this time?

We need to remember that at this time the population was still ‘recovering’ from the 12 day shift in the apparent dates of the seasons as a result of England changing its calendar so as to come into line with the Gregorian Calendar that had been promulgated to the Catholic world as long ago as 1582. This change had only finally taken place in England some ten or eleven years previously.

The change actually took place on 2 September 1752. That Wednesday evening, millions of British subjects in England Scotland and the Colonies went to sleep and woke up ‘twelve days later’. It was, of course, the British Calendar Act of 1751[xv], which had declared that the day after Wednesday the second would be Thursday the fourteenth.

Not only was there this change but the start of the year had changed too. Previously, in England, the day after 24 March 1642 was 25 March 1643. The Act changed this, so that the day after 31 December 1751 was 1 January 1752. As a consequence, 1751 was a short year - it ran only from 25 March to 31 December.

Such an adjustment would surely cause upset even in today’s more educated Britain. In the 18thC it must have been quite traumatic. Any help in getting to grips with these changes would certainly have been welcomed. Not only this but it should also be noted that Scotland had already partly made the change since they had already been observing the start of the year as 1st January since 1st January 1600. However, they made their calendar change at the same time as England. As if all this was not enough, some aspects like the tax year, only changed to the Gregorian Year in 1800. There were therefore several decades of varying difficulty. The Earl, particularly as a Scot, would have been very much aware of the confusion of ordinary folk over all this and he might well have used his interest and knowledge to devise this unique approach at Luton Hoo Walled Garden.

Some further thoughts

This explanation, whilst quite feasible, falters a little because the directional lines, although nearly in accordance with the above explanation are nevertheless not quite ‘spot-on’. Not only are some of the sun’s directional lines not quite at right angles to the walls of the Octagon but also the Octagon is itself not a ‘regular’ one, being squashed slightly in the N-S direction.

One might conjecture that there might be three reasons for this.

v Firstly, the astronomical situation is such that the actual directions of astronomical sun rise and sunset that we can calculate today for the 18thC at the latitude of Luton Hoo (and which are drawn on the image above) are simply not exactly the same directions of the sides of an octagon. They are close but not exact. This fact probably accounts for the small discrepancies in the NE, NW, E and W directions. They are nearly so but are not exactly so.

v Secondly, the observable directions of sunrise and sunset at this location in the 18thC will be different to the calculated astronomical events. This arises because Luton Hoo Walled Garden is not at sea level and the land it is on slopes to the South.

v Thirdly, the rather larger discrepancies observed for sunrise/sunset in the SE and SW direction in midwinter and the slightly squashed nature of the octagon may reflect the fact that the octagon might have been laid out on the ground using observed directions of sunrise and sunset – events which might be hard to see on the specific day in winter and hence they may be a day or so out – or of course a distant hill might delay sunrise from the astronomical time.

The walls could then have been laid out according to what had been observed rather than what could have been ‘calculated’. After all this wasn’t to be an astronomical observatory. Practical measures were used for most things in those days.

The size of the garden is such that the original-height walls opposite to sunrise would have been in sunshine almost immediately and those opposite sunset would have retained any sunshine almost to sunset. Maybe the garden’s large size and original wall height were chosen together for just this?

Later changes

The entire octagonal wall was raised at some later date by something like 3 feet and at some point too the garden was divided into two by a wall running NW - SE (as shown in the images above). A large garden such as this would after all easily permit an internal wall and with it would come increased productivity. The bricks used for the increase in height were slightly different to the originals and this difference can be seen today in the dividing wall, suggesting that the division came later or that the two were done at the same time. The reason for these additions isn’t clear though one might surmise that the dividing wall would have provided a much increased area of wall in morning sunshine and as well a similar area of wall that is in substantial shade and certainly shade from the noon sun. The dividing wall must surely have been used for plants since the watering system is continued along it. One might think too that both the dividing wall and the increase in height would also have provided much needed further protection from wind on what is after all a ‘hill top’ site. This would perhaps be especially so if by that time there had been some sort of change of use – perhaps to growing more food from plants that might have needed additional protection.

Finally, we might mention that in the 18thC there were ideas that some planting might be more successful if done on or around a full moon. Moonlight is simply a reflection of sunlight and a full moon occurs 12 hours behind noon with the direction coming from the South. The octagonal arrangement would still be a useful indicator for that.

We shall probably never know for sure the reasons for building the garden as it is, but the above shows that whatever they were, the octagonal walled garden certainly represented new technology in the running of a botanical garden.

Recent Addition - a Sundial!

An Analemmatic sundial was installed in 2013 to mark the tercentenary of the birth of Lord Bute.

Acknowledgement

I am delighted to acknowledge comment and research by Dr VL Thomson and the kind efforts of the volunteer staff of the Luton Hoo Estate in the preparation of this summary.

Patrick Powers

16.03.13, 05.03.17, 30.11.18

Appendix – Other known Octagonal gardens

1. Sledmere Octagonal Walled Garden

http://www.britishlistedbuildings.co.uk/en-167858-walled-garden-to-sledmere-house-sledmere

Historic England List entry Number: 1083805

Listing NGR: SE9334764763

Features:

House built in 1751 by Richard Sykes

Lat Long: 54.070662,-0.575495

Offset dividing wall running NE SW.

Aligned 7-8 degs clockwise from N-S.

Size across flats: N-S 98m, EW 92m, NW SE 94.114m NE SW

Slopes 124m to 118m West to East

Squashed Octagon. Possibly more of a walled parallelogram

2. Kinlochlaich House, Appin, Argyll, PA38 4BD Octagonal Walled Garden

http://www.kinlochlaichgardencentre.co.uk/

Scottish Designation: LB12367

Historic Scotland Building ID: 12367

Features

Garden built by John Campbell circa 1790

Lat Long: 56.566659,-5.355722

Aligned between 17 and 20 degs clockwise from N-S.

Size across flats: "N-S" : 66m and "E-W" 76m NE-SW : 72m, NW SE 78m

Slopes N-S from 30m elev to 24m

Garden Centre and plant nursery in the garden

3. Arbigland House, Lochfoot, Dumfries and Galloway DG2 8BQ

http://www.britishlistedbuildings.co.uk/sc-10372-arbigland-house-walled-garden-and-fruit-s/map

Scottish Designation: LB10398

Historic Scotland Building ID: 10398

Features

House built 1755

Lat Long 54.899407, -3.572173

More a chamfered rectangle than a true Octagon

Aligned 4-5degs anticlockwise from N-S

Size across flats: 88N-S and 80 EW.100m NW SE, 99m NE SW

Slopes 19m-15 in elev N-S

Glasshouse and fruit store

Literature Notes

Octagonal garden buildings were often inspired by the Grand Tour...Eg Mount Stewart, West Wycombe and Shugborough.

Regarding Shugborough: The shelter provided by enclosing walls can raise the ambient temperature within a garden by several degrees, creating a microclimate that permits plants to be grown that would not survive in the unmodified local climate.

Most walls are constructed from stone or brick, which absorb and retain solar heat and then slowly release it, raising the temperature against the wall, allowing peaches, nectarines and grapes to be grown as espaliers against south-facing walls as far north as southeast Great Britain and southern Ireland.

Movable blocks to control the movement of hot air in the heated wall at Eglinton Country Park.

The ability of a well-designed walled garden to create widely-varying stable environments is illustrated by this description of the rock garden in the Jardin des Plantes in Paris’ 5ème arrondissement, where over 2,000 species from a variety of climate zones ranging from mountainous to Mediterranean are grown within a few acres:

Wikipedia: The garden is protected from sudden changes in weather conditions and from harsh winds, thanks to its hollowed out terraces and the big trees. The gardeners make the most of the northern or southern exposures and the permanently shady areas of this little, sheltered valley. Within just a few metres, temperatures can range from 15 to 20 degrees C, what one would call a micro-climate.

Capability Brown was renowned for his inventiveness in Engineering landscapes and in his use of water. [xvi]

[i] The Earl lived 25 May 1713 – 10 March 1792

[ii] Notably also ‘History Home’ (http://www.historyhome.co.uk). NB Permission may need to be obtained to use the intellectual property of such sites in any publication.

[iii] See http://www.historyhome.co.uk/pms/bute.htm

[iv] See http://www.historyhome.co.uk/pms/bute.htm

[v] See http://www.historyhome.co.uk/pms/bute.htm

[vi] See http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Stuart,_3rd_Earl_of_Bute

[vii] See http://www.historyhome.co.uk/pms/bute.htm

[viii] See http://bit.ly/2mqAwP7

[ix] Gray T. (2003) 'Walled gardens and the cultivation of orchard fruit in the south-west of England'

[x] Wilson, C. A. (Ed.) (2003). The Country House Kitchen Garden 1600-1950. Stroud: Sutton Publishing Limited. Page 2

[xi] Campbell, S. (2006). Walled Kitchen Gardens. Princes Risborough: Shire Publications Ltd. Page 7

[xii] Wilson, C. A. (Ed.) (2003). The Country House Kitchen Garden 1600-1950. Stroud: Sutton Publishing Ltd. Page 4

[xiii] Campbell, S. (2006). Walled Kitchen Gardens. Princes Risborough: Shire Publications Ltd. Page 8 and others

[xiv] Campbell, S. (2006). Walled Kitchen Gardens. Princes Risborough: Shire Publications Ltd. Pages 27-28

[xv] See http://www.legislation.gov.uk/apgb/Geo2/24/23/contents

[xvi]Engineering the Landscape – Capability Brown’s role. http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/107312/18/WRRO6login.pdf